|

Human Head Lice.

Introduction to Lice. Louse Gallery. |

Main Page 1 of 1 |

|

Human Head Lice.

Introduction to Lice. Louse Gallery. |

Main Page 1 of 1 |

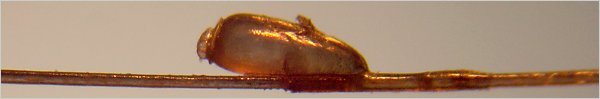

"The louse has killed more human beings than has any other insect, with, perhaps, the malaria mosquito excepted. Historically, lice are the major insect vector of disease in temperate and cold lands, as mosquitoes are in hot ones."Louse is a term applied to an insect which fulfils two conditions. It must be an external parasite of a warm-blooded animal (bird or mammal), and it must spend its entire life cycle on that animal. The human head louse attatches its eggs to the base of a hair, close to the scalp. The nymph which hatches from the egg develops to an adult after three moults, and dies within two or three weeks, after a life of constant feeding, mating and egg-laying. Lice are spread by physical contact between humans. When they are removed from the host's head and placed under the microscope, they appear sluggish and clumsy, but at the temperature of the human scalp and amongst the hairs for which their bodies are adapted, they are quite active, and can easily change hosts during brief moments of contact. Thus they spread most rapidly between children. In this way, the average louse may spend its day on several heads. The other common lice of the human body are the clothing lice and pubic lice. Interbreeding between head and clothing lice is possible, but under normal conditions, the three types favour different regions of the body, and live distinct and separate lifestyles. Head lice are increasingly common amongst the well-scrubbed children of the middle classes, having been previously associated with the poorest in society sharing a more crowded and less hygienic lifestyle. Humans are not the only creatures which thrive in a more hygenic environment. Their removal is beset with misapprehensions and old-wives tales. Washing with medicated shampoos and similar offerings is not much use -- unless the medication is left in contact with the lice long enough to kill them. Anything short of this amounts to using sub-lethal dosage to guarantee the evolution of resistant lice. Also, it is almost impossible to drown a louse, at least during the course of a normal shower or bath. They have been known to survive four days clinging to the body hairs of animals constantly submerged or drenched with water. The most effective solution is normal hygiene plus frequent combing of the hair. Fine-tooth combs are effective for removing the lice, and frequent grooming with a normal comb also controls the infestation by removing some lice and inflicting injury on others which cling tenaciously to hairs in their efforts to resist being dislodged. Lice do not regenerate lost limbs, and any louse which has lost a leg due to combing (or scratching) will die very shortly thereafter. In some societies, head lice are controlled by applying oil to the hair. The oil suffocates the growing louse by sealing the air vents in the operculum of the egg casing. Click for a diagram of human lice. Click for Hooke's illustration of a louse from Micrographia (1665).

Many thanks to Ms. Ada Zimmermann for the supply of the specimens. |