|

Worms: Nematodes.

Introduction to Nematode Worms. Nematode Worm Galleries. |

Main Page 1 of 1 |

|

Worms: Nematodes.

Introduction to Nematode Worms. Nematode Worm Galleries. |

Main Page 1 of 1 |

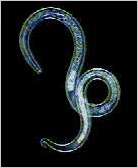

The nematodes are (along with copepod crustaceans) frequently described as "probably the most numerous animals on Earth". Some 80,000 species are described  in the literature; possibly a million exist.

They live in the soil, in the oceans and fresh water, and are found as internal parasites of most animals and many plants.

in the literature; possibly a million exist.

They live in the soil, in the oceans and fresh water, and are found as internal parasites of most animals and many plants.

It has also been said that if the animals of the world (apart from nematodes) were to dematerialize, their ghostly forms would be recognizable by the populations of nematodes which inhabit their tissues. There are certainly regions of the world where this would be true. The larger parasitic nematodes are referred to as roundworms, and the smaller parasites as threadworms. They have cylindrical bodies with no trace of segmentation. Chaetae (bristles) are seen only in some of the marine forms. The outer elastic cuticle is shed four times during the life of the worm. The mouth is at or near the anterior end, and the gut is a straight non-muscular tube with an anus at or near the posterior end. A muscular pharynx with a bulbous swelling towards the end is observable in the microscopic forms. The sexes are separate -- there is no hermaphroditism in the nematodes, but in certain species the females at certain stages reproduce parthenogenetically. They have no blood system, no respiratory system and no cilia. They also have no circular muscle, which means they are not capable of the contractions and constrictions shown by other worms, and typically move in a series of tight S-shaped curves which are fascinating to observe (See movie sequence below). The parasitic worms in this gallery have been identified to species by scientists at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, who also kindly supplied the specimens. The free-living nematodes are found in moist soil and bodies of fresh water, and are mostly less than a millimetre in length. The population density of nematodes in some marine sediments may reach as much as 20 million per square metre (!) and although these extreme numbers are not encountered in fresh water, almost any sample taken from the debris of the pond bottom will contain numerous specimens. All microscopic nematodes are remarkably similar in appearance, so they are easily distinguished from other worms, but their identification to species is a task for the expert. Here is a diagram of a typical nematode (53KB). Brugia malayi (found mainly in the far east) and Wuchereria bancrofti (in tropical and subtropical regions) are the two species of filarial nematodes (long and thin worms) associated with the worm infections known as lymphatic filariasis and its gross manifestation, elephantiasis. The young infective worms, called third-stage larvae, are transferred to uninfected animals by blood-feeding mosquitoes which have fed upon infected animals. The transfer is not immediate -- the worms which infect the insect take some days to migrate from the insect's flight muscles to the mouthparts (effectively the hollow bottom lip of the mosquito) where introduction to a new host can take place. Here is a diagram of the mosquito's mouthparts. Once introduced into the host animal, the worms mature into adults of separate sexes in the lymphatic system, usually of the lower limbs. Here the adult worms can cause inflammation and physical obstruction of the lymph vessels. Great swelling of the tissues may result, especially in the legs and the scrotum in men, causing the condition described as elephantiasis. The large female worms produce thousands of young worms, called microfilariae, that move out of the lymphatics into the blood stream. In the evening these young worms begin to move into the peripheral blood stream where they can be swallowed by mosquitoes biting at night. The microfilariae taken up in the blood meal tear through the mosquito's stomach before migrating to the flight muscles where they settle down to mature into the large infective larvae seen in the photographs below.

An interesting aside in this dismal scenario is that the mosquitoes are also the victims of the worm infection. Those which harbour a particularly large number of microfilariae are usually too weakened and uncoordinated to achieve penetration, thus preventing the development of their eggs.

The photographers who took the pictures of the infected mosquitoes had undergone a course of antifilarial drugs in the week preceding the photo sessions, and in order to reduce even further the risk of contracting an infection, the mosquitoes had been infected with Brugia pahangi, a parasite of cats but not humans. In any case, a successful infection can only result if both male and female worms are introduced, enabling mating to occur in the host bloodstream. The pictures below are of Brugia pahangi, very similar in appearance to the Brugia species which infect humans. River blindness is the common name for Onchocerciasis, an infectious microfilarial disease widespread in Africa and other countries such as Mexico and Guatemala. It is caused by the nematode worm Onchocerca volvulus and is spread by blood-feeding flies of the genus Simulium. Blindness is caused when the worms invade the eyes. |

|||||||||||